I have a confession to make. I’m a pack rat. I save everything. From ticket stubs and boarding passes to funny notes from friends. I justify this behaviour by telling myself that these things have an emotional value and represent a moment in my journey through this world.

And of course, this has spilled over in my digital life as well. Yes, I’m one of those people with so many tabs opened in my browser that it’s hard to tell what each of those tabs contain. The thought of my browser randomly crashing freaks me out. The day I discovered the One-Tab Google Chrome extension, my life changed.

So naturally, it took a while to get used to the idea of self-destructive messaging. Text, photo and video messages which are deleted shortly after they are read or viewed. Ephemeral content like this has a brief existence. Intended to share a thought or a moment in time, it lives a short, yet purposeful life.

Ephemeral messages try to recreate that natural conversation feeling. Just like having coffee with a friend, users don’t have to worry about being recorded. Since these conversations aren’t meant to be archived and referenced, there’s a sense of ‘temporariness’. As a result, users don’t have to invest a lot of time and thought into what they communicate. Less effort means sharing is easy and conversations are quick and frequent.

Although SnapChat is the most popular player in the ephemeral messaging space right now, numerous others have emerged to get a piece of the pie. They all approach the ‘fleeting’ nature of messaging slightly differently, but there are some overarching themes when it comes to designing for ephemerality.

Give users control

One of the basic principles of user centered design: letting the user drive their own experience. Although the messages are disposable in nature, allowing the user to have some control over their messages creates a sense of comfort and builds trust.

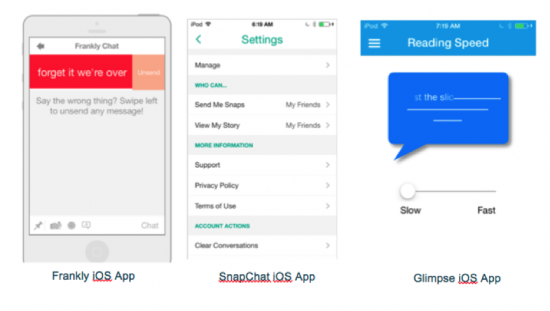

For example, Frankly allows users to retract their messages in case they changed their mind or made a mistake. SnapChat users can select how long their messages are visible for and which contacts are able to view their ‘stories’ (a collection of snapchats). Glimpse messenger reveals the message only a few words at a time. It allows the user to adjust the speed at which the message is displayed to control the rate at which the message is consumed.

Be transparent

With ephemerality comes a little bit of mystery. Not having the content stored and the increased frequency of communication creates a sense of casualness, leading users to share anything from goofy selfies to sensitive information. Clearly communicating how the information is handled and who gets to see it becomes crucial. In addition, any permissions requested such as access to contact lists, camera or microphone, also require disclosure of how that access will be used. It all goes back to building trust.

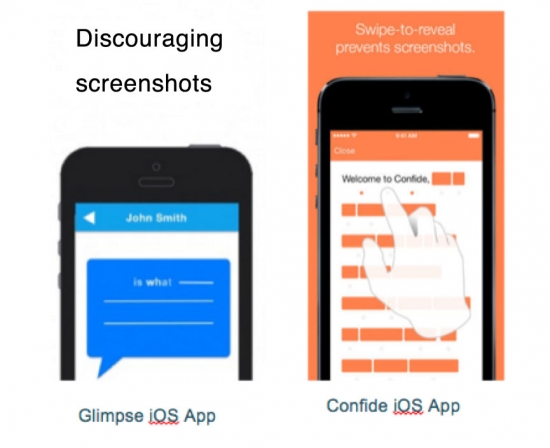

Prevent screenshots

Knowing that there will always be users who will try to hack the system, it's a good idea to build in measures to prevent any actions that go against the ephemeral nature of the experience.

For example, text in Glimpse messenger disappears while it’s being typed, creating a very small window of opportunity for the receiver to read it. Confide prevents screenshots by covering the text with blocks, which are only removed by swiping them individually.

Create a sense of ‘temporariness’

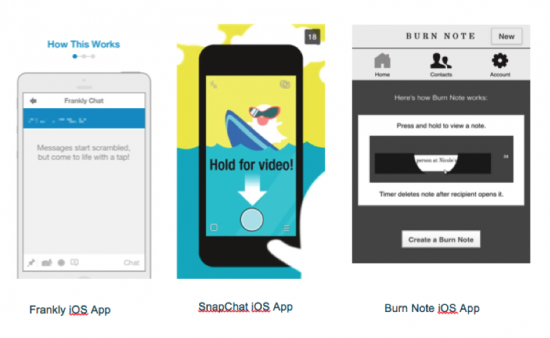

By partially revealing the message, Glimpse, Confide and Burn Note create a sense of temporariness and urgency. Part of the message disappears while it is being consumed. Since the message is not visible in its entirety, it requires the receiver to pay attention so they can make sense of it.

‘Tap to display’ and ‘hold to record’ interactions also create a sense of impermanence. They require the user to maintain a physical contact with the device in order to consume or create a message. Disconnecting from the device, even for a second, disables the process. Frankly uses this concept in a creative way by scrambling the sender’s message, which the receiver can the unscramble by tapping and holding it.

Allow users to ‘live a moment’

The great thing about in-person conversations is that they are synchronous. The flow of the conversation is highly dependent on how one reacts to the verbal and non-verbal cues of the communicators. If ephemeral messaging services are meant to emulate in-person conversations, there has to be an element of synchronicity and shared experience.

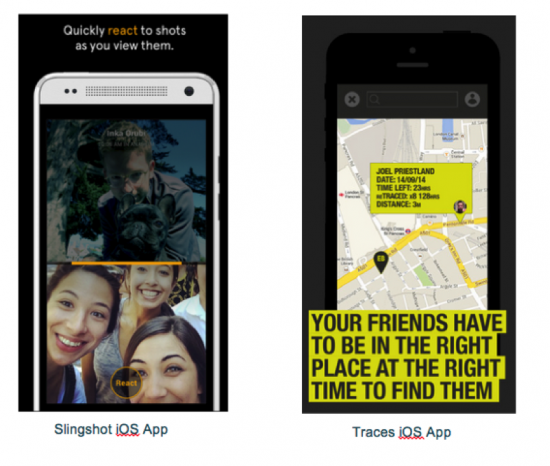

Facebook’s Slingshot aims to synchronize the experience of sending and receiving a message. In order to retrieve a message, users have to record their reaction to the message at the same time. The idea is to encourage interaction by incorporating a crucial element of the conversation: the receiver’s reaction.

Traces is a different kind of ephemeral messaging app. Currently in beta and only available in the UK, it allows users to send a message to someone, which can only be picked up by the receiver when they are at the same location where the message was sent from. Although this type of communication is asynchronous in nature, it’s an interesting attempt to share and re-live a moment experienced by someone in the past based on a geographic location.

Ephemeral messaging is definitely here to stay. In a hyper connected and heavily documented world, these messages are a call to live in the present. They encourage us to share moments from our individual journeys, live the ones experienced by our friends, and pack lightly for the adventure ahead.